Long Method#

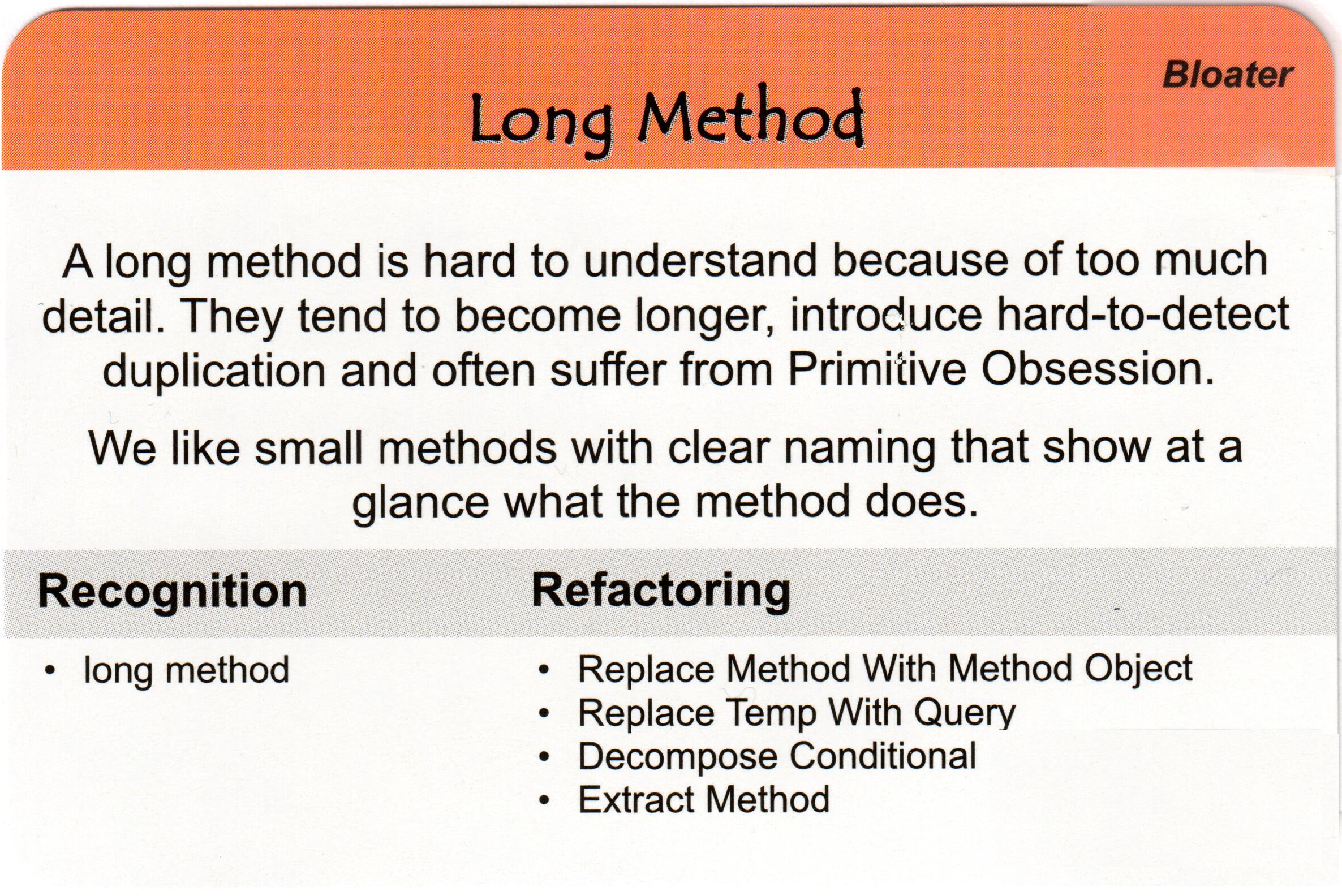

The “Long Method” refactoring problem refers to a code smell where a method or function becomes excessively long, making it harder to understand, maintain, and test. Long methods often contain too many lines of code or perform multiple tasks, violating the Single Responsibility Principle.

The presence of long methods can lead to several problems:

Reduced readability: Long methods can be challenging to read and comprehend, especially when they contain multiple nested conditions, loops, or complex logic. It becomes difficult to grasp the purpose and flow of the code, making it harder for developers to understand and modify.

Decreased maintainability: When a method is long and complex, it becomes more fragile and difficult to modify. Making changes or adding new functionality becomes risky, as it can introduce unintended side effects or errors that are hard to trace. Additionally, debugging long methods can be time-consuming and error-prone.

Lack of reusability: Long methods often perform multiple tasks, making it harder to reuse the code in other parts of the program. Code reuse is an important aspect of maintainable and efficient software development, and long methods hinder this goal.

Difficulty in testing: Testing long methods can be challenging, as there are typically multiple execution paths and potential outcomes to consider. Writing comprehensive test cases to cover all possible scenarios becomes more complex and time-consuming.

To address the “Long Method” code smell, the recommended solution is to refactor the method into smaller, more focused methods. Each method should have a single responsibility, making it easier to understand, test, and modify. The goal is to improve readability, maintainability, and modularity by breaking down the complex logic into smaller, reusable components (see also Functions are Friends and Many More Much Smaller Steps).

By refactoring long methods, developers can enhance code quality, make the codebase more maintainable, and improve collaboration among team members. It allows for better organization and abstraction of code, making it easier to reason about and maintain over time.

public class Calculator {

public double calculateTotalPrice(List<Item> items) {

double totalPrice = 0.0;

for (Item item : items) {

// Perform complex calculations

// ...

// ...

// ...

// ...

totalPrice += item.getPrice();

}

// Perform more complex calculations

// ...

// ...

// ...

// ...

// Perform additional operations

// ...

// ...

// ...

// ...

// Return the final result

return totalPrice;

}

}

// Usage

Calculator calculator = new Calculator();

double totalPrice = calculator.calculateTotalPrice(items);

public class Calculator {

public double calculateTotalPrice(List<Item> items) {

double totalPrice = 0.0;

for (Item item : items) {

totalPrice += calculateItemPrice(item);

}

return totalPrice;

}

private double calculateItemPrice(Item item) {

// Perform complex calculations

// ...

// ...

// ...

// ...

return item.getPrice();

}

}

// Usage

Calculator calculator = new Calculator();

double totalPrice = calculator.calculateTotalPrice(items);

In the clean code examples, the long method calculateTotalPrice is refactored into smaller, more focused methods (calculateItemPrice in this case). The logic related to calculating individual item prices is extracted into a separate method, improving readability and adhering to the single responsibility principle.

By breaking down the logic into smaller, self-contained methods, the code becomes more modular, easier to understand, and maintain. Each method now has a clear purpose and can be independently tested and modified if needed. The resulting code is more readable, less error-prone, and adheres to better software design principles.