Conditional Complexity#

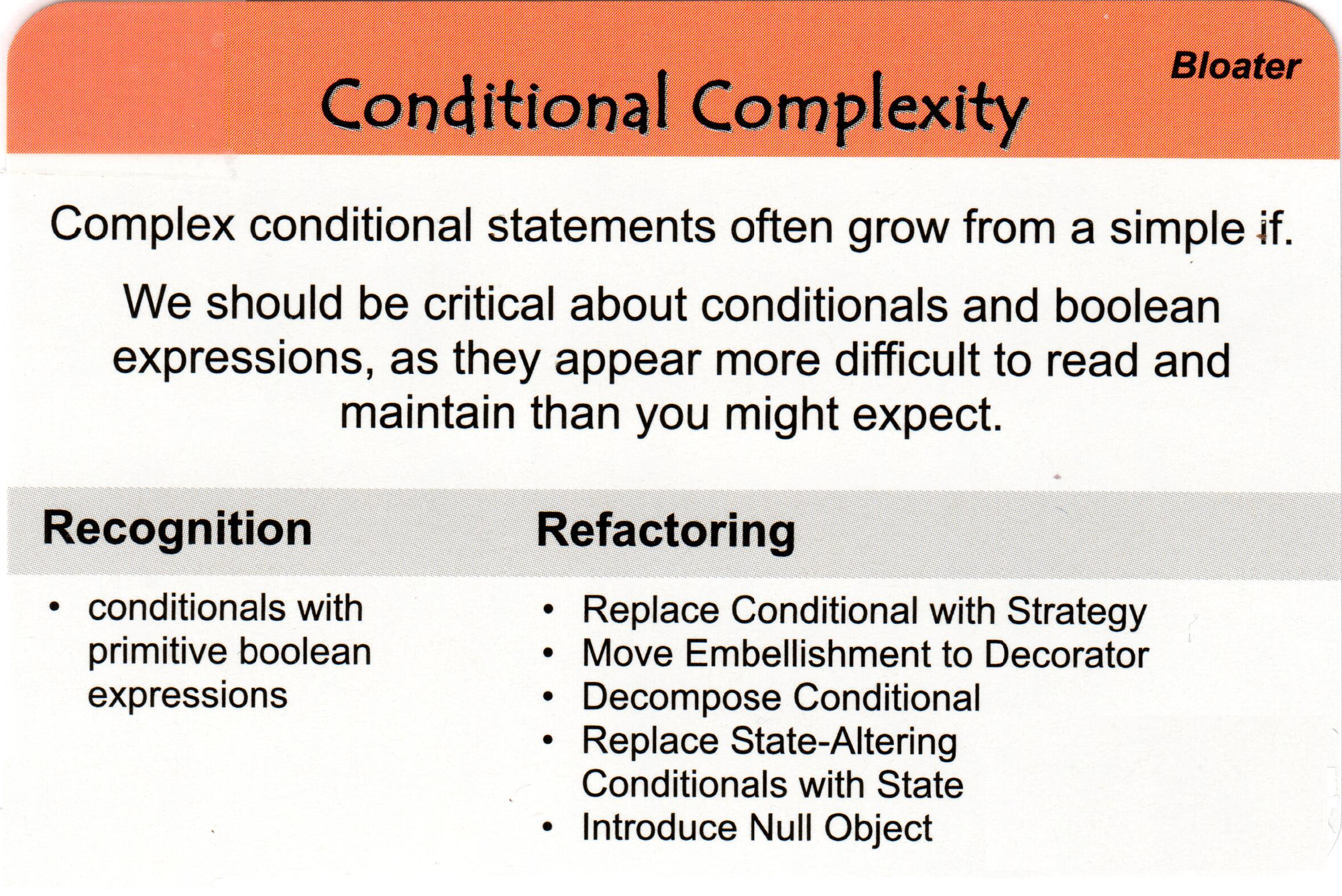

In software development, a code smell refers to any symptom in the source code that indicates a potential problem or weakness in the design or implementation of a program. Conditional complexity can be considered a code smell when it exceeds a reasonable level, making the code harder to understand, maintain, and test.

High conditional complexity is a code smell because it often indicates that the code might be too convoluted, poorly structured, or lacking in abstraction. Some common manifestations of conditional complexity as a code smell include:

Long Nested If-Else Blocks: Deeply nested if-else blocks can become difficult to follow and understand. It becomes challenging to determine the flow of the program and identify all possible execution paths.

Large Switch-Case Statements: Extensive switch-case statements with numerous cases can indicate that the code is trying to handle too many different scenarios within a single block, potentially leading to increased complexity.

Multiple Ternary Operators: The overuse of ternary operators (i.e., inline if-else expressions) can make the code concise but challenging to read, especially when used excessively within a single line.

Complex Boolean Expressions: Complex boolean expressions with multiple conditions and logical operators can be hard to comprehend and may lead to errors.

Duplicate Conditional Logic: Repetitive conditional logic scattered across different parts of the codebase can indicate a lack of code reuse and lead to maintenance headaches.

Overwhelming Test Coverage: High conditional complexity can make it challenging to achieve comprehensive test coverage, leading to gaps in testing and potential bugs slipping through.

As a code smell, high conditional complexity suggests that the code could benefit from refactoring or redesign to improve its readability, maintainability, and overall quality. Some ways to address conditional complexity as a code smell include:

Extract Methods or Functions: Break down complex conditional blocks into separate methods or functions with descriptive names. This can make the code more modular and easier to follow.

Replace Conditionals with Polymorphism: Consider using polymorphism or other design patterns to replace complex conditionals with more straightforward and extensible structures.

Simplify Boolean Expressions: If possible, simplify complex boolean expressions by breaking them down into smaller, more manageable parts.

Use Guard Clauses: Replace nested conditionals with guard clauses (early returns) to handle exceptional cases first and reduce indentation levels.

Apply Design Principles: Follow software design principles such as SOLID and DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) to improve code organization and eliminate duplication.

By addressing conditional complexity as a code smell, developers can create cleaner, more maintainable codebases that are easier to understand and evolve over time.

Examples#

Python#

class Exporter:

def export(self, export_format: str):

if export_format == 'txt':

self.export_as_txt()

elif export_format == 'csv':

self.export_as_csv()

elif export_format == 'xml':

self.export_as_xml()

elif export_format == 'xls':

self.export_in_xls()

...

class Exporter:

def export(self, export_format: str):

exporter = self.get_format_factory(export_format)

exporter.export()

def get_format_factory(self, export_format: str):

if export_format in self.export_format_factories:

return render_factory[export_format]

raise MissingFormatException

...

...

Java#

Suppose we have a LoanApprovalService class responsible for approving loans based on various conditions, such as the applicant’s credit score, income, and loan amount.

public class LoanApprovalService {

public boolean approveLoan(Applicant applicant, double loanAmount) {

if (applicant.getCreditScore() >= 700 && applicant.getIncome() >= 50000 && loanAmount <= 200000) {

// Code for approving the loan

return true;

} else {

// Code for rejecting the loan

return false;

}

}

}

In this example, the conditional logic for loan approval involves multiple conditions combined with logical operators (&&). As more conditions are added, the complexity of the conditional statements increases, making the code harder to read and maintain.

To simplify the conditional complexity, we can leverage the Strategy design pattern. We’ll create separate strategies for each condition and use them to determine loan approval.

public interface LoanApprovalStrategy {

boolean approveLoan(Applicant applicant, double loanAmount);

}

public class CreditScoreApprovalStrategy implements LoanApprovalStrategy {

@Override

public boolean approveLoan(Applicant applicant, double loanAmount) {

return applicant.getCreditScore() >= 700;

}

}

public class IncomeApprovalStrategy implements LoanApprovalStrategy {

@Override

public boolean approveLoan(Applicant applicant, double loanAmount) {

return applicant.getIncome() >= 50000;

}

}

public class LoanAmountApprovalStrategy implements LoanApprovalStrategy {

@Override

public boolean approveLoan(Applicant applicant, double loanAmount) {

return loanAmount <= 200000;

}

}

We create separate strategy classes, each implementing the LoanApprovalStrategy interface. Each strategy focuses on a specific condition for loan approval.

public class LoanApprovalService {

private List<LoanApprovalStrategy> approvalStrategies;

public LoanApprovalService() {

approvalStrategies = List.of(

new CreditScoreApprovalStrategy(),

new IncomeApprovalStrategy(),

new LoanAmountApprovalStrategy()

);

}

public boolean approveLoan(Applicant applicant, double loanAmount) {

for (LoanApprovalStrategy strategy : approvalStrategies) {

if (!strategy.approveLoan(applicant, loanAmount)) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

}

We modify the LoanApprovalStrategy to use the strategy pattern. The service holds a list of approval strategies and iterates over them to check each condition. If any condition fails, the loan is rejected. Otherwise, it is approved.

By refactoring the code using the strategy pattern, we simplify the conditional complexity. Each condition is encapsulated within its own strategy, making the code more modular, readable, and maintainable. Adding or modifying conditions becomes easier as we can introduce new strategies or modify existing ones without impacting the overall structure of the loan approval service.

Replace Conditionals with Polymorphism#

Sure! Let’s consider a simple example where we have different types of animals, and we want to calculate their sounds based on their types. Instead of using conditional statements to determine the sound of each animal, we can use polymorphism to achieve the same functionality. Here’s how you can do it in Java:

Using Conditionals (without polymorphism):

class Animal {

String type;

public Animal(String type) {

this.type = type;

}

public String makeSound() {

switch (type) {

case "Dog":

return "Woof!";

case "Cat":

return "Meow!";

case "Duck":

return "Quack!";

default:

return "Unknown animal";

}

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Animal dog = new Animal("Dog");

Animal cat = new Animal("Cat");

Animal duck = new Animal("Duck");

Animal unknown = new Animal("Unknown");

System.out.println(dog.makeSound()); // Output: Woof!

System.out.println(cat.makeSound()); // Output: Meow!

System.out.println(duck.makeSound()); // Output: Quack!

System.out.println(unknown.makeSound()); // Output: Unknown animal

}

}

Using Polymorphism:

abstract class Animal {

public abstract String makeSound();

}

class Dog extends Animal {

@Override

public String makeSound() {

return "Woof!";

}

}

class Cat extends Animal {

@Override

public String makeSound() {

return "Meow!";

}

}

class Duck extends Animal {

@Override

public String makeSound() {

return "Quack!";

}

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Animal dog = new Dog();

Animal cat = new Cat();

Animal duck = new Duck();

System.out.println(dog.makeSound()); // Output: Woof!

System.out.println(cat.makeSound()); // Output: Meow!

System.out.println(duck.makeSound()); // Output: Quack!

}

}

In the polymorphic approach, we define an abstract class Animal with an abstract method makeSound(). We then create concrete subclasses (Dog, Cat, Duck) that extend the Animal class and implement their specific sound behavior.

By using polymorphism, we eliminate the need for conditionals to determine the sound of each animal. This makes the code more extensible and maintainable, especially if we want to add new animal types with different sounds in the future.

Now there is a problem with this code. Can you tell what it is?

The example I provided does not follow the Open–Closed principle. The Open–Closed principle states that software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension but closed for modification.

Let’s come up with a better example that adheres to this principle by using polymorphism to handle different animal sounds without modifying the existing code.

First, we’ll define the basic structure of the animal classes:

interface Animal {

String makeSound();

}

class Dog implements Animal {

@Override

public String makeSound() {

return "Woof!";

}

}

class Cat implements Animal {

@Override

public String makeSound() {

return "Meow!";

}

}

class Duck implements Animal {

@Override

public String makeSound() {

return "Quack!";

}

}

Now, we’ll create a separate class responsible for making animal sounds. This class will be open for extension, as we can add new animal types without modifying the existing code:

class AnimalSoundMaker {

public String makeSound(Animal animal) {

return animal.makeSound();

}

}

Finally, in our main program, we can use the AnimalSoundMaker class to make different animals produce their sounds without modifying the Animal classes:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

AnimalSoundMaker soundMaker = new AnimalSoundMaker();

Animal dog = new Dog();

Animal cat = new Cat();

Animal duck = new Duck();

System.out.println(soundMaker.makeSound(dog)); // Output: Woof!

System.out.println(soundMaker.makeSound(cat)); // Output: Meow!

System.out.println(soundMaker.makeSound(duck)); // Output: Quack!

}

}

With this approach, we have decoupled the sound-making behavior from the animal classes. The AnimalSoundMaker class is open for extension because we can add new animal types (implementing the Animal interface) without having to modify the existing AnimalSoundMaker class. This adheres to the Open–Closed principle, making our code more maintainable and easier to extend in the future.

Now it is absolutely possible to use the Factory Method design pattern to improve this code, but it will probably also raise the Conditional Complexity of the code again. So, I will leave it up to you to decide whether you want to use the Factory Method design pattern or not.

class Animal:

def make_sound(self):

pass

class Dog(Animal):

def make_sound(self):

return "Woof!"

class Cat(Animal):

def make_sound(self):

return "Meow!"

class Duck(Animal):

def make_sound(self):

return "Quack!"

def make_animal_sound(animal):

return animal.make_sound()

if __name__ == "__main__":

dog = Dog()

cat = Cat()

duck = Duck()

print(make_animal_sound(dog)) # Output: Woof!

print(make_animal_sound(cat)) # Output: Meow!

print(make_animal_sound(duck)) # Output: Quack!

Also known as#

Repeated Switching

Switch Statements

Prefer polymorphism to conditional logic